|

Routes to Yorktown

The Washington & Rochambeau march to Yorktown, in conjunction with the arrival of the French fleet from the Caribbean, has long been recognized as a military masterstroke, which resulted in victory at Yorktown and brought an end to the long struggle for American independence. Just 36 days after a decision was made to attack Cornwallis in Virginia, allied forces were assembling on the York River 300 miles away. To have moved armies that far, that fast was a remarkable feat. To have outwitted the enemy and successfully completed campaign without provoking a counterattack was a miracle.

The route of Rochambeau's march to Yorktown across New Jersey is well known from maps, journals and military records. Food for an army of 5,000 plus as many as 1,000 servants and civilian workers, and forage for no less than 1,500 horses and 600 oxen had to be provided at each campsite along the way.

|

Because the area crossed was not enemy territory, the French could not simply help themselves to whatever they needed. Everything had to be bought and paid for with cash up front. So, in addition to giving Washington a numerical advantage at Yorktown, the French army presence provided a most welcome injection of hard cash into the war-ravaged New Jersey economy.

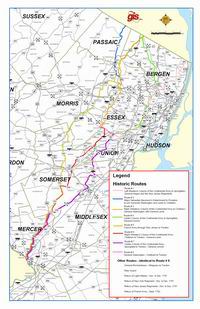

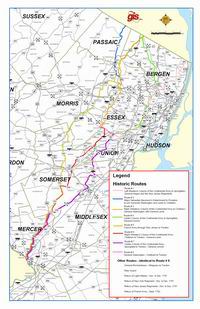

On the map of the "March through New Jersey", the heavy line on the left indicates the French troop movement. The French left Suffern, New York on August 25th, proceeded 12 miles down the Ramapo Valley, and camped at Pompton Plains. The following day, a march of 15 miles brought them to Whippany where they camped two days, before marching 14 miles through Morristown to Bullion's Tavern (Liberty Comer) the next day. From Bullion's Tavern, they marched 13 miles the next day brought them to Somerset Court House (Millstone) and a like distance through the Millstone Valley the next day to Princeton. A final 12 miles to Trenton completed their march across New Jersey on September 1. Washington and Rochambeau went ahead of the troops to meet with the Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia.

|

March Through New Jersey

(click on Map Index link below)

|

Unlike the well planned and well documented French march across New Jersey, routes taken by American forces can be pieced together only from fragmentary evidence. Washington did not issue written orders, and his units did not need detailed instructions. New Jersey was by then familiar territory to the American Army, and they readily made their way to Trenton and then on further south where some crossed the Delaware to Pennsylvania and others traveled downriver by boat.

An important consideration was the potential reaction of the strong British garrison in New York City. Sir Henry Clinton, commander of British forces, had to be kept guessing as to the ultimate objective of allied troop movements. Misleading letters were deliberately dispatched via routes where they would likely be intercepted by Clinton's intelligence network, and conflicting rumors were set abroad. Only a handful of trusted senior officers were told that they were headed for Virginia.

The broken lines on the map indicate several routes taken by American forces. One was an advance guard sent marching southward through Bergen County by way of various routes including Paramus and Belleville, near Newark, a move certain to be noticed by the British and make it appear the focus was on New York. Another American column marched from Mahwah, by way of Oakland and Wayne, to Springfield. At Chatham bake ovens were built to prepare bread for the French army and to suggest a possibility attack on New York by way of Staten Island.

While the tactics worked in that they kept Clinton confused, the multiple routes of the American troops have also left historians confused. Although much has been gleaned from fragmentary evidence in letters and journals, and from a trail of IOUs and damage claims left in their wake by the chronically cash-starved Continentals, there are many gaps in the picture.

Even Washington himself has been difficult to trace. As the heavy black line indicates, he set out along the same route as the French, and then took a more easterly course, stopping at Chatham before passing through Springfield, New Brunswick, Princeton, and Trenton.

|

The Maps of Louis-Alexandre Berthier (1753-1815)

Berthier's maps - numbering 111 - were executed, presumably soon after the event, from information and sketches made on the spot while Berthier was accompanying Rochambeau's Army in America. The maps include the French Army's camp sites on the southward march from Newport, Rhode Island, to Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, and on the return march northward in the summer and autumn of 1782.

The Berthier who drew the maps - later to become famous as one of Napoleon's marshals and chief military advisers - was born in Versailles in 1753, one of the four sons of Jean - Baptiste Berthier, military engineer and cartographer, chief of the Royal French Army Map Service. Following in his father's footsteps, young Louis-Alexandre Berthier entered the army and received training in military engineering. He thus acquired proficiency in map-making according to the highest standards of the day. The Berthier maps, now at Princeton, reflect the best French cartography of the period.

It is possible that part of the credit for these maps should go to Berthier's younger brother, Charles Louis Berthier (1759-1783). As related in Louis-Alexandre's journal, the two brothers were together during the entire American campaign; Charles-Louis died in 1783, before reaching home, as a result of wounds received in a duel while the French fleet was off the Dutch colony of Curaçao.

See below, examples from the Berthier collection (click on Image to open in a new tab) and visit the Berthier Map Collection for additional information.

|

|

|

|

|

|